image description: An early sunrise in late summer coastal Maine, the sky streaked with orange and the crevices in the land filled with a river of mist. This side of the mist is a picturesque tool shed surrounded by carefully curated “wild” vegetation. Photograph copyright 2016 by Sparrow Rose Jones

This is a re-blog of a blog post originally made on 7 October, 2014. An edited version of this essay appears in the excellent anthology: The Real Experts: Readings for Parents of Autistic Children, edited by the incomparable Michelle Sutton and available for purchase from Autonomous Press or a library or bookseller near you (and if it is not available at a library or bookseller near you, please do ask them to provide copies. Thank you.) This essay also appeared as a guest post on the Diary of a Mom blog.

Content note: compliance-based training, labeled as therapy. Lasting trauma and PTSD from ill-advised treatments. Sexual abuse and rape. The lasting effects of ABA (Applied Behavioral Analysis). The risk of being told “not my ABA.”

This week, I watched a community implode. I’m not going to talk about that, though, because it was very painful to watch people I love being treated so badly. But a lot of the implosion centered around a topic I do want to talk about. That topic is ABA – Applied Behavior Analysis, a common type of therapy for Autistic children. I watched people fight around in circles, chasing their metaphorical tails. It will take some time and lots of words to unpack this topic, but I hope you will stick with me on this because it’s so important and there is a lot that needs to be understood here.

Here’s the argument in a nutshell. It gets longer, angrier, and much more detailed than this, but I am exhausted just from reading the fighting, so I’m boiling it all down to two statements. And both statements are correct.

Autistic adult: “ABA is abuse.”

Parent of Autistic child: “I’m not abusive and my child is benefitting greatly from ABA therapy.”

You read me right: both statements are correct. That is part of what I need to unpack today. I think the best place to start is with the fact that both people above are using the term “ABA”, but what they are actually talking about are usually two different things. First we need to define ABA.

Well, actually, first I want to put people at ease. Parents — it’s got to be painful to feel like a whole group of people are ganging up on you and telling you that you are abusing your child. You love your child. You want the best for your child. You are spending thousands of dollars out of pocket to try to give your child the best possible chance in life. You worry about your child. You feel like you never even knew what love was until your child came along. You are not abusing your child. And if something you are doing is harming your child, you want to know about it and stop it. It hurts to be told that you are abusive toward the child you love so much.

And my fellow Autistics — you grew up feeling picked apart. You were subjected to things that harmed you. You still have PTSD today from things that may have been done with your best interests at heart but were actually quite damaging. You don’t fit in to the world around you and the adults who were charged with your care when you were growing up were stumbling around in the dark when it came to trying to figure out how to raise a child like you were. It is triggering to see that so many of the things that hurt you when you were growing up are still being said and done to and about children who are so very much like you were when you were their age. You want to stop the cycle of pain and you want children to grow up happy, healthy, and loved. It frightens and angers you to see many of the “best practices” that Autistic children today live with.

And there is a good chance that the two of you — the Autistic adult and the parent of an Autistic child — are not even talking about the same thing when you say “ABA.” Major organizations (particularly Autism Speaks) have lobbied hard for Medicaid and insurance companies to cover ABA therapy for Autistic children. As a result, many therapists now call what they do “ABA,” even in cases where the actual therapy is very different from genuine ABA, in order to have their services covered by insurance. It’s similar to the philosophy of therapists I’ve known who don’t believe in diagnosing mental illness but put a name on their patients’ struggles anyway because many insurance policies only pay for therapy if the treatment is for a diagnosis listed in the DSM. That’s the main point that I wanted to make, but there’s still a lot to say on this topic.

If almost everything is being called “ABA” then what is actual ABA? And why do Autistic adults say it is abusive? What sort of warning signs should parents be watching for? What is harmful about certain practices? Those are a lot of questions to answer, but I will do my best. Bear in mind that I’m not a therapist — ABA or otherwise — and I’m not a parent. I’m one Autistic adult, one person coping with therapy-induced PTSD, one person exhausted by the all-out war I see every day between people like me and people who love people like me, one person who wants to see a better world for everyone (but, I admit, especially for Autistic people.)

ABA was developed by Dr. Ivar Lovaas. As a 1965 Life Magazine article explains, the core theory of ABA was that a therapist, “forcing a change in a child’s outward behavior” would, “effect an inward psychological change.” The article says, “Lovaas feels that by I) holding any mentally crippled child accountable for his behavior and 2) forcing him to act normal, he can push the child toward normality.”

Much has changed, but this core premise of Lovaas’ work remains solid. ABA’s core belief is that forty hours per week of therapy geared toward making a child externally appear as “normal” as possible will “fix the brokenness” inside that made the child behave that way. ABA believes in an extreme form of “fake it until you make it,” and because it is behaviorism at its most pure — that is, a psychological science that treats internal processes as irrelevant to function (Lovaas said, “you have to put out the fire first before you worry how it started”) — it treats behavior as meaningless and unwanted actions rather than as communication.

This approach is troubling for many reasons.

ABA strongly emphasizes the importance of intensive, saturated therapy and insists that it is crucial to get 40 hours a week of therapy for very young children. Think for a moment how exhausted you, a grown adult, are after 40 hours of work in a week and you will begin to understand why we get so concerned about putting a three-year-old child through such a grueling schedule. Being Autistic doesn’t give a three-year-old child superpowers of endurance. Forty hours a week of ABA is not just expensive, it is painfully exhausting. ABA maintains a schedule like this with the intention of breaking down a child’s resistance and will.

I understand that you are afraid for your child. Their future is unknown. You are worried about their ability to live a fulfilled life. You are worried about their ability to have self-supporting work and be taken care of after you pass on. And I understand that this fear, coupled with a deep desire to give your child the best you can give them, can lead you to accept the ABA attitude of “more is better.” But stop a moment and think about the capacity for sustained focus of the average three-year-old and consider what a therapy that tries to double (or more) that capacity is doing to a child. If you stress a child out or even traumatize them with extreme therapies, you are paradoxically increasing the chances of incapacitating PTSD in the child’s future. Yes, you want your child to develop as much as they are able to develop and you want them to enjoy their life and hopefully provide for themselves, but exhaustion and trauma are not going to aid those sorts of development.

Worse than the exhaustion of so many hours of therapy, though, is the heavy focus on making a child “indistinguishable from his peers.” The main goal of ABA is to make a child LOOK normal. This is insidious for a few reasons. first, it is the best way to get the parents to continue to co-operate with the therapists for many years. Of course you are going to be moved to tears if the therapist gets your child to look you in the eye or say “Mommy” to you or sit at the table and eat a meal without fidgeting or melting down. Of course you will feel like the therapist is making progress and healing your child. That is a very natural response. So you will see the progress and you will want to continue with ABA therapy and you will be very defensive when adults Autistics online suggest that what is happening in your home might be a bad thing. What was bad were fights every mealtime. What was bad was never hearing your child’s voice. What was bad were the judgmental or pitying stares you and your child got when you went out in public and people saw your child spinning around or flapping her hands or becoming so anxious you were forced to leave your groceries unpurchased and flee the store.

But if your child is getting classic ABA therapy, what you are seeing is an illusion. And what looks like progress is happening at the expense of the child’s sense of self, comfort, feelings of safety, ability to love who they are, stress levels, and more. The outward appearance is of improvement, but with classic ABA therapy, that outward improvement is married to a dramatic increase in internal anxiety and suffering.

ABA therapists are trained to find out what your child loves the most and hold it ransom. Often, it’s food. If your therapist suggests withholding food as a form of behavioral therapy, run screaming. That is harmful. If your child’s therapist will not allow you to remain in the room during a session (they will usually tell you that your presence will be a distraction that will keep your child focused on you instead of on the therapy they need to be paying attention to) that is a big warning sign. If you are able to witness your child’s therapy sessions and your child is spending a lot of time crying or going limp or flopping on the floor or showing signs you recognize as indicators of anxiety or fear, beware the therapy. If the therapist insists on pushing forward with the therapy when your child is crying or going limp instead of giving your child recovery time, run screaming. Therapy that trades your child’s sense of safety in the present for a promise of future progress is exactly the sort of thing that Autistic adults mean when they talk about abusive therapy.

Therapy should make your child better, not traumatize them, possibly for many years, potentially for the rest of their life. A therapist might tell you that “a little crying” is a normal thing, but I was once an Autistic child and I can tell you that being pushed repeatedly to the point of tears with zero sense of personal power and knowing that the only way to get the repeated torment to end was to comply with everything that was asked of me, no matter how painful, no matter how uneasy it made me feel, no matter how unreasonable the request seemed, knowing that I had no way out of a repeat of the torment again and again for what felt like it would be the rest of my life was traumatizing to such a degree that I still carry emotional scars decades later. It doesn’t matter whether the perpetrator is a therapist, a teacher, a parent, or an age-peer: bullying is bullying.

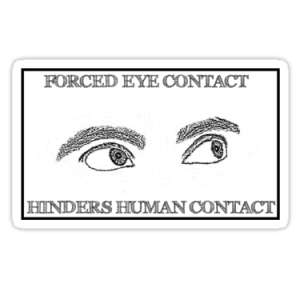

In my opinion, the goal of therapy should be to help the child live a better, happier, more functional life. Taking away things like hand flapping or spinning is not done to help the child. It is done because the people around the child are uncomfortable with or embarrassed by those behaviors. But those are coping behaviors for the child. It is very important to question why a child engages in the behaviors they do. It is very wrong to seek to train away those behaviors without understanding that they are the child’s means of self-regulation. When considering whether you have made a wise choice in what therapy you are providing your child or not, you want to always remember a few cardinal rules: behavior is communication and/or a means of self-regulation. Communication is more important than speech. Human connection is more important than forced eye contact. Trust is easy to shatter and painfully difficult to re-build. It is more important for a child to be comfortable and functional than to “look normal.”

Work on things like anxiety and sensory issues first. Work on getting better sleep (both you and your child). Things like eye contact can come later, much later, and only if your child is comfortable with them. There are work-arounds. Lots of people fake eye contact. Lots of people have good lives with minimal or no eye contact. But forcing a child to do something that is deeply painful and distressing for no reason other than to make them look more normal is not just unnecessary, it is cruel.

I live two blocks from a behavioral clinic and I frequently walk several blocks out of my way to avoid walking past it because of the kinds of things I have seen when walking past the clinic. Let me tell you about the last thing I saw there, the thing that made me decide that I would rather walk an extra half-mile than risk seeing more ABA therapy on the sidewalk in front of the clinic.

A mother and father came out of the clinic with a little girl, around 7 years old by my best guess. Mother said, “Janie (not the actual name), look at me.” Janie didn’t look at her mother. The mother said to the father, “you know what to do,” and the father took hold of Janie and turned her head toward mother, saying, “look at your mother, Janie.” Janie resisted, turning her head away and trying to pull out of her father’s hands.

Mother crouched down and Father lifted Janie’s whole body up, laying her across Mother’s knee, face up. “Look at your mother, Janie,” father said. “Look at me, Janie,” Mother said. Janie began to whimper. Her body was as stiff as a board. Father held her body firm and Mother took hold of Janie’s head, “look at me, Janie,” Mother said.

I was glued to the sidewalk. I didn’t want to see any more but I couldn’t look away, couldn’t walk away. Janie began to moan and thrash her body. Father’s hands held her body steady as she kicked and flailed. Mother’s hands held Janie’s head steady. Both kept urging Janie to look at her mother. Janie’s moans turned to screams but neither parent let her go.

Finally, Janie’s entire body went limp with defeat. She apparently made eye contact because Mother and Father began to lavish praise on her. “Good girl, Janie. Good eye contact. Good girl. Let’s get some ice cream now.” Janie’s limp body slid to the sidewalk where she lay, sobbing. Father picked her up and carried her to the car, the whole way praising her submission. “Good eye contact, Janie.”

(This image – a drawing of eyes looking away with the caption

“Forced eye contact hinders human contact” – is a sticker and is also

available as a light t-shirt or dark t-shirt in adult and children’s sizes.)

What did Janie learn that day? I’ll give you a hint: it was not that people are more trusting of those who make good eye contact. It was not that she will appear more normal and thus fit into society better if she makes good eye contact. It wasn’t even that Mom really loves it when Janie connects with her through the eyes like that.

Janie learned that adults can have whatever they want from her, even if it hurts and even if they have to hurt her to get it. Janie learned that her body does not belong to her and that she has to give others access to it at any time, for any reason, even if she wasn’t doing anything that could hurt herself or others. Janie learned that there is no point in resisting and that it is her job to let others do what they want with her body, no matter how uncomfortable it makes her.

You may think I’m exaggerating or making this out to be more extreme than it is, but stop for a moment and imagine years of this therapy. Forty hours a week of being told to touch her nose and make eye contact and have quiet hands and sit still. A hundred and sixty hours a month of being restrained and punished when she doesn’t want to touch her nose and being given candy and praise when she does touch her nose for the 90,000th time. Nearly two thousand hours a year of being explicitly taught that she does not own her body and she does not have the right to move it in ways that feel comfortable and safe to her. How many years will she be in therapy? How many years will she be taught to be a good girl? To touch her nose on command? To make eye contact on demand? Graduating to hugs, she will be taught that she is required to hug any adult who wants a hug from her. She will be punished when she does not hug and praised and fed when she does.

And who will protect her from the predator who wants to hug her? Who will teach her that she is only required to yield her bodily autonomy for her parents and therapists but not for strangers? What if the predator turns out to be one of her therapists or parents? How will she resist abuse when she has had so many hours of training in submission? Therapy is an investment in the future, but ABA therapy is creating a future for Janie of being the world’s doormat. Is that the future Janie’s parents want for her?

If your child’s therapist believes it is more important for your child to comply with every command than to have any control at all over his or her body, run screaming. And don’t forget that a layer of training does not change the underlying neurology. ABA uses the same methods and theories as dog training and if I train my dog to shake hands, it doesn’t make him more human. It just makes him a dog who can shake hands. Similarly, if you train an Autistic to make eye contact and not flap their hands and say “I love you, too” and stay on task, it just makes them into an Autistic who can fake being not-autistic with some relative measure of success. Underneath the performance is still an Autistic brain and an Autistic nervous system and it is very important to remember that. Being trained to hide any reaction to painful noises, smells, lights, and feelings doesn’t make the pain go away. Imagine years of living with pain that you have been trained to hide. How long would it last before you broke down? Some Autistics last an amazingly long time before they break down and burn out.

And intensive ABA therapy will also teach a child that there is something fundamentally wrong and unacceptable about who they are. Not only is that child trained to look normal, they are trained to hate who they are inside. They are trained to hate who they are and hide who they are. They will work very hard to hide who they are, because they have learned to hate who they are. And as a result, they will push themselves to the brink of destruction. And when they finally crumble from years of hiding their sensory pain and years of performing their social scripts and blaming themselves every time a script doesn’t carry them successfully through a social situation, they will be angry at themselves and blame themselves for their nervous breakdown and autistic burn-out.

All those years of ABA therapy will have taught them that they are fundamentally wrong and broken; that they are required to do everything authority demands of them (whether it’s right or wrong for them); that they are always the one at fault when anything social goes wrong; that they get love, praise, and their basic survival needs met so long as they can hide any trace of autism from others; that what they want doesn’t matter.

Now you know what to watch for. Your child’s therapist may use the term “ABA” in order to get paid, but they might not be doing these harmful, degrading, abusive things to your child at all. If your child’s therapist is respecting your child, not trying to break down the child’s sense of self and body-ownership, treating behavior as communication rather than pointless motions that need to be trained away, valuing speech but not at the expense of communication, giving your child breaks to recover and not over-taxing their limited focusing abilities . . . then they can call their therapy anything they want to, but it is not ABA. (And hold on to that therapist! They are golden!)

And I hope that the next time you hear an Autistic adult say that ABA is abuse, you are compassionate. Remember the suffering so many of us endured. Know that we say those things because we love your children and want to help them. We do not say them because we hate you and want to call you abusers. We don’t hate you at all and we want to help you. Sometimes we are clumsy in how we go about it, because, well, we are Autistic and communication difficulties are part of that package. But know that when we attack ABA, we are not intending to attack you. We want your child to sleep through the night and laugh with joy and become toilet trained (on whatever schedule their bodies can handle — don’t forget that we tend to be late bloomers), and have a healthy, happy, productive, love-filled life.

We want you to rejoice in parenting and connect with your children on a deep and meaningful level. When an Autistic adult says “ABA is abuse,” you might be tempted to hear, “you are abusing your child.” But that is not what we are saying. Next time you hear an Autistic adult say “ABA is abuse,” please hear those words as, “I love you and your child. Be careful! There are unscrupulous people out there who will try to convert the fear you feel for your child’s future into money in their pocket at the cost of your child’s well-being.”

And if you are a therapist and you are upset when we say “ABA is abuse”, know that we are not talking about you . . . unless you are using shock punishments or making children endure long hours of arduous therapy beyond their ability to cope or teaching children that they do not have the right to say who can have access to intimacy with their body or not (and forced eye contact is a particularly nasty violation of a person’s control over their bodily intimacy.) If you are not the kind of therapist who we are talking about when we talk about the harm of therapy, then we are not talking about you! Thank you for being one of the good guys. We need more like you. Teach others what you know. Spread the love and help change the world, please!

Thank you for reading all of this. I know it was a lot of words, but this is such an important topic. The children are the future and I don’t have words to explain how painful it is when I see Autistic adults being verbally bullied and abused because they are trying to help the children by helping parents to understand more about the lived experience of autism and more about the kinds of things that can be very harmful to Autistic lives. I had over a decade of therapy in my childhood and much of it was not good therapy and I am explicitly damaged because of it. When I say ABA is abuse — when we Autistic adults say ABA is abuse — we are speaking from a collective wisdom gained through painful experiences that have left lasting scars on us. We don’t want anyone else to have to go through the pain we have gone through. Please respect where we are coming from and please do not add to the trauma by attacking us for trying to help others. Thank you.

=========

Edited to add: if you would like to see some video examples of helpful vs. harmful therapies, check out this blog post I made a month later on that topic:

Helpful vs. Harmful Therapies: What Do They Look Like?

Recent Comments