Traffic Laws Are Not “Everyday Examples of ABA”

Introduction

You’ve probably heard it before: “We all experience ABA every day!” The go-to example? Stopping at a stop sign. Supposedly, we stop because we’ve been conditioned—by tickets or crashes or social pressure—and that’s Applied Behavior Analysis in action. Simple, right?

Except… no.

This tidy analogy shows up everywhere from therapist training programs to parent workshops to casual online debates. It’s trotted out to make ABA seem natural, universal, and harmless. The message is clear: if stopping at a stop sign is ABA, then ABA must be fine.

But that’s not how ABA works.

In this essay, I’m going to take that example for a spin. First, we’ll look at what ABA actually involves. Then we’ll imagine what it would really look like if stopping at stop signs were an example of ABA methods. And finally, we’ll dig into why misusing examples like this doesn’t just muddy the waters—it actively manipulates public understanding in ways that harm autistic people.

Because if following traffic laws is ABA in action, I’m owed a massive backlog of M&Ms.

What ABA Actually Involves

Applied Behavior Analysis isn’t just any old cause-and-effect learning. It’s a structured, clinical intervention rooted in behaviorist psychology. In practice, ABA relies on clearly defined goals, repeated teaching opportunities (called “discrete trials”), detailed data collection, and carefully managed reinforcement schedules.

If someone’s learning a skill through ABA, it’s not happening by osmosis. There’s a program written for it. There’s an “operationalized” behavior goal—something observable and measurable, like “Will raise hand to request help in 4 out of 5 trials over two consecutive sessions.” There are cues (called SDs), prompts if needed, and a consequence following each attempt: a reward for success or a correction for errors.

The process is deliberate, monitored, and graphed. It’s not just about learning—it’s about shaping behavior through external reinforcement until the target behavior becomes consistent, often without regard for internal motivation, context, or consent.

This isn’t how most people learn to stop at stop signs.

If Stop Signs Were Taught via ABA

Let’s say you really were taught to stop at stop signs through ABA. Here’s how that might look.

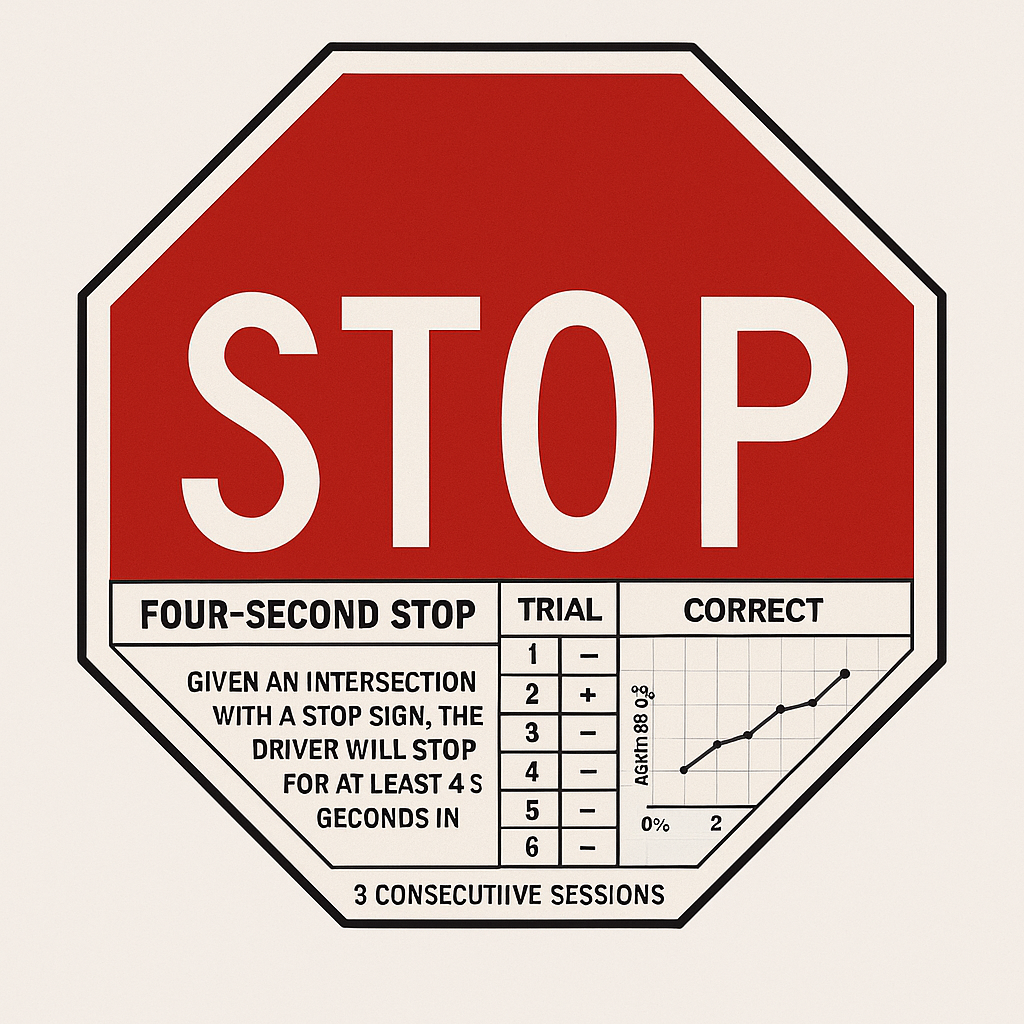

First, a behavior analyst would write a program goal:

“Given the visual cue of a red octagonal sign, the learner will bring the vehicle to a full stop behind the white line in 4 out of 5 trials across 3 consecutive sessions, with no more than one verbal prompt.”

You’d begin with structured instruction. A therapist—or in this case, probably your driving instructor—would deliver a discriminative stimulus (SD), like “There’s a stop sign ahead.” If you failed to stop, they’d use a prompt—maybe a verbal reminder like “Brake now,” or a gesture pointing to the pedal. If you did stop (even with a prompt), you’d get a reinforcer: “Great job!” or maybe a tangible reward like a piece of candy.

Every trial would be documented:

• Trial 1: Prompted stop – Partial Physical Prompt – Reinforced

• Trial 2: Independent stop – Reinforced

• Trial 3: No stop – Error correction procedure initiated

Your instructor would collect data for each discrete trial, likely on a clipboard balanced on their knee. They’d graph your performance over time to determine whether the behavior was increasing, whether prompts could be faded, and whether the skill was generalizing across different intersections.

Only after weeks of consistent data showing mastery would the stopping behavior be considered “acquired.”

At no point would you be expected to just get it because of logic, empathy, social norms, or internal motivation. That’s not how ABA works.

Why the Analogy Fails

So why do people keep saying that stopping at a stop sign is an example of everyday ABA?

Because it sounds good. It sounds simple. It reassures nervous parents and skeptical stakeholders that ABA is nothing to fear—just common sense in action.

But here’s the problem: it isn’t true.

Stopping at a stop sign is rule-governed behavior, not behavior shaped through operant conditioning. Most people stop at stop signs not because they were systematically reinforced over hundreds of discrete trials, but because they were told, “This is the law,” maybe saw a diagram in a driver’s manual, and internalized the rule.

They’ve likely seen a car crash—on the road, on the news, or in a driver’s ed video—and they understand the stakes without needing to personally experience any kind of aversive. We stop because we know it’s expected, because it would piss other drivers off if we didn’t, because we don’t want to get stopped by the police, and because we’ve absorbed the potential consequences both intellectually and viscerally. That’s not ABA. That’s culture, cognition, and social learning.

ABA is built on observable behaviors, external rewards, and structured repetition. It’s not a casual consequence you heard about once and filed away in your mind—it’s a targeted intervention, complete with data sheets and reinforcer hierarchies.

When people use the stop sign analogy, they collapse all of that complexity into a feel-good metaphor. It’s not just misleading—it’s strategically misleading.

The Harm of Misleading Normalization

When people claim that stopping at a stop sign is “just like ABA,” it’s not an innocent misunderstanding. It’s a deliberate rhetorical move—a way of normalizing a highly structured and often coercive intervention by comparing it to everyday life.

This kind of sleight-of-hand is designed to build trust where skepticism is warranted. It encourages parents to accept ABA without asking hard questions. It assures policymakers and funders that what they’re supporting is just good, common-sense learning. And it silences autistic people who raise concerns, because if “everyone experiences ABA,” then our objections must be overblown.

But autistic people don’t object to rules. We object to being subjected to intense, dehumanizing compliance training disguised as care. We object to interventions that treat our natural communication, movement, and affect as problems to be corrected. We object to being turned into data points in someone else’s binder.

By flattening the distinction between real-life learning and structured behavioral intervention, these analogies obscure power, consent, and the actual lived experience of being on the receiving end of ABA. Stories of “Stop Sign ABA” are not harmless—they’re manipulative. And they serve the system, not the person.

Conclusion

Applied Behavior Analysis is a specific, technical method. It’s not a vibe. It’s not a metaphor. And it’s not the reason you know how to drive.

When people reach for easy analogies to defend ABA, they’re not simplifying—they’re obscuring. They’re smoothing over the hard edges of a controversial practice and offering comfort at the expense of truth. But autistic people deserve better than rhetorical sugar-coating. We deserve honesty, accuracy, and respect for the reality of our lived experiences.

So the next time someone tells you that stopping at a stop sign is ABA in action, ask them for your operational goal, your discrete trial data, and the thousands of M&Ms you’re owed for a lifetime of lawful driving. Better yet, tell them: If that’s ABA, then I’m Pavlov’s dog.

Recent Comments