[image description: a terrapin in the middle of the road on a hot, sunny day. His skin is dark with bright yellow stripes and his shell is ornate, covered with swirls of dark brown against a honey-yellow background. The terrapin is rushing to get across the street and his back leg is extended from the speed and force of his dash toward freedom. photo copyright 2017, Maxfield Sparrow.]

I hate meltdowns. I hate the way they take over my entire body. I hate the sick way I feel during a meltdown and I hate the long recovery time — sometimes minutes but just as often entire days — afterward when everything is too intense and I am overwhelmed and exhausted and have to put my life on hold while I recover

I hate the embarrassment that comes from a meltdown in front of others. I hate the fear that bubbles up with every meltdown. Will this be the one that gets me arrested? Committed? Killed?

Meltdowns, Like Shutdowns, Are Harmful But Necessary

We Autistic adults and teens put a lot of energy into figuring out what will lead to a meltdown and working to avoid those things whenever possible. Parents of younger Autistics also put a lot of energy and work into figuring these things out, both to try to keep triggering events out of their child’s life and to try to help their child learn how to recognize and steer around those triggers themselves. Outsiders who don’t understand will accuse us of being overly avoidance and self-indulgent and accuse our parents of spoiling and coddling us.

I have written about how shutdown can alter brain function in unwanted ways. Meltdowns also have their dangers and can alter brain function over time. A meltdown is an extreme stress reaction and chronic stress can damage brain structure and connectivity.

But meltdowns serve a purpose, just as another unpleasant experience that can also re-wire the brain if it continues chronically and unabated — pain — also serves an important and very necessary purpose.

Pain is an alarm system that helps us avoid bodily damage and urges us to try to change something to protect our body. While pain is usually unwanted and something we seek to avoid, without pain we would not live very long because we would not have such a strong drive to eliminate sources of damage to our bodies.

Meltdowns are alarm systems to protect our brains.

That idea is so important I gave it its own paragraph. And I’ll say it again: without meltdowns, we would have nothing to protect our neurology from the very real damage that it can accumulate.

So often, I see researchers and other writers talking about meltdowns as if they were a malfunction or manifestation of damage. I strongly disagree. It is easy for someone outside of us to view a meltdown that way because they see an unpleasant outburst that makes their lives more unpleasant or difficult to be around. They see someone who appears to be over-reacting to something that’s not such a big deal as all that. They see someone immature who needs to grow up, snap out of it, or get a “good spanking” to teach them to behave.

When someone doesn’t experience the hell it is to be the person having the meltdowns, they can easily misunderstand and misjudge what it actually happening.

Meltdowns Are A Normal Response To Sensitivities

Let me ask you something: this is a thought experiment and you don’t have to actually do this, but you might understand better if you actually follow along physically. Take your finger and poke the softer flesh on the inside of your thigh with it so that you are pressing the tip of your fingernail into your thigh. Don’t actually damage yourself! You’re just looking for a reference sensation. Poke it about as hard as you might press a button to ring someone’s doorbell.

If you have long, sharp fingernails that might have hurt a little bit (I hope you were careful. The goal here is not to injure yourself — just to create a physical sensation.) It was a quick poke, so it probably didn’t even leave a mark behind, no matter how long your fingernails are.

Now do the same thing to your gums, either above or below your teeth, in that area between your teeth and the inside of your lips. Oh! You couldn’t even poke it as hard, could you? Do be gentle with your gums, please. I repeat, this is not about harming yourself. You don’t even have to poke yourself at all if you don’t want to. You know your thighs and gums. You know without lifting a finger that I am telling you the truth when I say your gums are much more sensitive than your inner thigh.

And you are not “over-reacting” when you have more pain response in your gums than in your thigh, right? It’s easier to hurt your gums so your reaction to the same stimulus is much more intense when it is applied to your gum than to your thigh. You are not self-indulgent or spoiled. You don’t need a good spanking to get over how sensitive your gums are. You just need to take extra care that things don’t poke you in the gums.

So what’s my point? If you are not Autistic — and even more so if you are pretty close to neurotypical — your neurological wiring is more like your thigh. Life pokes at you a lot and you don’t even notice it. Much of life’s poking is fun for you. Some pokes are less recreational but present satisfying challenges. So when you see an Autistic person having a meltdown you might not even recognize the pokes they have been processing all day long because you don’t even feel them.

But our Autistic neurological wiring is more like your gums. Except not even that predictable. Some of our senses may be “hyporesponsive” and we need to stimulate them to be aware that they are even functioning. Some of us spin around or pace in circles. Some of us move our hands or fingers in ways that make us feel better. Some of us blast loud music with a heavy bass and drum component to it. Some of us rock back and forth. Our wiring demands more input than the world’s regular pokes can give us.

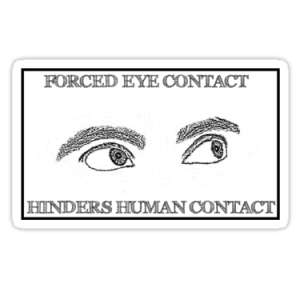

Some of our senses are “hyperresponsive” and we need much less stimulation. Life’s pokes are like fingernails grinding into our gums and we need to make it stop because we cannot bear the pain. Loud sounds or high-pitched sounds get to some of us. Others are overwhelmed by the struggle to understand speech when more than one person is talking at the same time. Some can’t stand textures of fabrics or foods.

Most people I know are a complex mixture of hyporesponsiveness and hyperresponsiveness. Most people I know have some senses that are both hypo and hyper responsive, changing over time. I can’t give you any single idea of a sensory pattern for an Autistic neurology because we each have our own combinations of needs.

Normal Human Variation Includes Variant Emotional Sensitivity Levels

But when it comes to meltdowns, it’s not just sensory input (or lack thereof) that will set off an Autistic’s neurological warning system and throw us into meltdown. What inspired me to write about this topic today was reading something I had written a year ago. I spent a few months living in an emotionally abusive situation last year. The man I was living with for a brief time figured out very quickly how to manipulate my compliance triggers. He even commented specifically on how easy it was for him to physically subdue me once he spotted the compliance “fish-hooks” that childhood had left embedded in me.

I’m not going to go into much detail about what he did for the same reason that I shy away from going into much detail about my decade of childhood therapy. I am working on removing those hooks from my flesh. The last thing I want to do is instruct others as to where those hooks are embedded and how to use them to steer me like a puppet.

My point in mentioning the incident at all is that I realized after the fact that my meltdowns had been sending me a very clear message I should have heeded immediately. Instead, I did what I always do: I interpreted my meltdowns as a sign of how damaged I was and how much I needed help to gain self-control. Most of my life, I’ve allowed lovers to convince me to try to medicate my meltdowns into submission. I have hated them because they seemed to illustrate how flawed and awful I was. My thought process went like this: I melt down because I’m Autistic and meltdowns are frightening and horrible and who would want to be my romantic partner? I can’t blame people for treating me badly and wanting to get away from me because look at these meltdowns!

My experience last year helped me to finally realize that I was looking at things backwards.

I don’t melt down because I’m Autistic.

I melt down because something in my environment is intolerable and I am having a normal reaction of pain and/or anxiety. That pain can be from something physical, like an intolerable temperature in the room or a sound that is piercing my eardrums and making me nauseated. Or it can be something emotional, like internal feelings of frustration or external abuse.

Everyone has meltdowns. It’s not just an Autistic thing. But our wiring is different, just like the wiring is different between your thighs and your gums. Some things that make neurotypicals meltdown don’t bother me. A whole heaping lot of things that don’t bother neurotypicals make me meltdown terribly. I’m not deficient in some way; I’m wired differently.

Meltdowns Protect Us From Harmful Situations And People

One of the things I learned last year is that even when I can’t recognize abuse because I have alexithymia, even when I can’t recognize abuse because my compliance training is kicking in full force, my body and nervous system will send me the message with repeated meltdowns.

What I wrote a year ago:

If I have lots of shouting, freak-out, PTSD meltdowns when we spend time alone with each other, yes it’s an Autistic thing. But it also means you’re regularly doing something messed up.

An isolated meltdown could just be a random convergence of awful that has nothing to do with you, but if a pattern develops, you’re probably gaslighting me, mistreating me, abusing me, or generally taking nastily unfair advantage of that same autistic neurology that makes me unable to recognize I’m being abused or mistreated until I see the pattern of meltdowns.

All my life I’ve been told, and believed, that losing my shit was a personal shortcoming I should work to overcome.

I now realize it’s actually my body/brain’s alarm system letting me know something’s seriously wrong in my life. Something bad that needs to be fixed, like yesterday, if not sooner.

I finally realized all this today. Everything suddenly connected.

And in an instant, I no longer hate my meltdowns. I think I might actually love them. They protect me.

So… I still do hate meltdowns. More specifically, I hate having meltdowns. They are hard on me, physically and emotionally. They are embarrassing, messy, frightening.

But I am grateful that my body has a way to tell me when I’m in a bad situation, even if my mind is not capable of figuring it out yet. I vow to respect and honor my meltdowns. This is not the same as excusing my behavior. This is not the same as giving myself free reign to do whatever, whenever.

I still want to do whatever I can to avoid having a meltdown. I still want to work on my ability to detect a meltdown on the horizon and remove myself to safety before things go too far.

But I also vow to listen to my meltdowns and pay closer attention to my triggers. Meltdowns teach me what my nervous system can handle and what is too much for me. Meltdowns teach me how to take care of myself. Meltdowns teach me what my nervous system needs. Meltdowns highlight areas of my life that are not on track.

Sometimes my depression shows me that something is wrong in my life but sometimes depression is just like a wildfire, burning out of control. The same with anxiety. But I have learned that meltdowns are always highlighting something I need to address.

Meltdowns protect me. Some aspects of my neurology make me more vulnerable. Some remnants of childhood experiences leave me more vulnerable. Meltdowns fill that gap and send me messages about my life that can help me protect myself.

While I will never enjoy having a meltdown, I promise I will always value the protective gift meltdowns bring me.

Recent Comments