[image description: lens flare from the sun. In the upper right corner, the sun blazes brightly, sending penetrating rays down into the forest and culminating in a green arc at the lower left. Perhaps it could be taken as a visual symbol of the penetrating light of wisdom? Taken November 19, 2016, in the Devil’s Millhopper Sinkhole, Gainesville, Florida. Copyright Sparrow R. Jones]

Privilege. I’ve seen so many arguments crop up when people start talking about privilege. I understand where people are coming from: if you’re white and impoverished, you probably don’t feel very privileged, right? You probably think something like, “oh, right. This white skin sure hasn’t done much for me. I’m living in a run-down trailer while Kanye West has millions of dollars. Don’t tell me about privilege!”

I’ve seen that argument, or some variation on it, so many times over the years. The argument is incorrect because it comes from not understanding what is meant when someone talks about “white privilege” or just “privilege.”

For starters, the word “privilege” means an advantage and most people don’t feel like they have much advantage in life. “Membership has its privileges” “he’s a privileged character.” People think of the word “privilege” as something that means you were ‘born with a silver spoon in your mouth.’

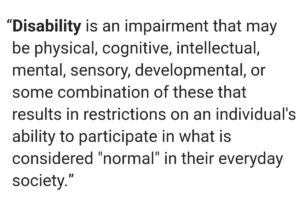

Yes, that is one definition of privilege, but when the word is being used to talk about social issues, it just means a specific edge, often (but not always) brought about through society’s stigmatized view of different types of people. If you don’t belong to one of the groups of people who are especially looked down on, hated, and/or feared you have privilege…at least in that area of your life.

It doesn’t have to be a huge edge. Privilege is not an absolute and it is not like an on/off switch where you’re either a millionaire or a skid-row bum.

But there’s something even more important than the amount of any specific type of privilege you have: the interaction between different amounts of privilege or lack of privilege in your life. Let me talk about something that might (or might not) be a new word for you: intersectionality.

Yes, it’s one of those academic words. But I’m going to break it down now and hopefully it will help you understand how you can be down on your luck or even at the bottom-of-the-barrel and still have some kinds of privilege.

Every single one of us is the result of intersections (combinations/interactions) of many different personal identities. For example, here are some of my identities:

- white

- female at birth

- transgender/transmasculine

- alternate sexuality (very complicated to explain. Let’s just call it grey asexual for now.)

- Autistic

- multiply physically disabled

- not mobility impaired/not a wheelchair user

- multiply neurodivergent/neurologically disabled (N24 in addition to autism)

- psychologically disabled (C-PTSD, Anxiety, Depression)

- middle-class upbringing (college-educated parents, good childhood nutrition, etc.)

- highly educated (both self-educated and at university)

- poor/homeless

- middle-aged

Each of those identities has a different amount of privilege or lack of privilege.

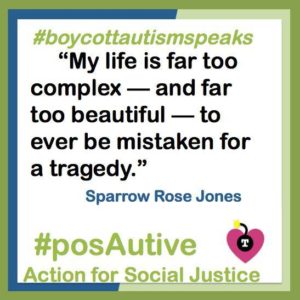

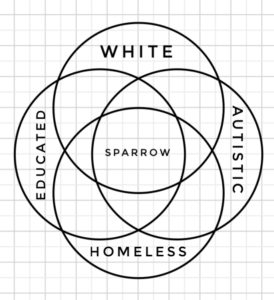

Let me draw you a picture of my own intersectionality. I have way too many identities to put them all in one diagram, so I’m just going to talk about four of them in this diagram:

[image description: a drawing of four circles that overlap. On the edges, each of those four circles is labeled: ‘WHITE’, ‘AUTISTIC’, ‘HOMELESS’, ‘EDUCATED’. In the center, where all four identity circles overlap, is the word ‘SPARROW’.]

This diagram illustrates four of those identities I listed above: white, Autistic, homeless, and educated. I put my name in the center where all the circles overlap, to show that I am a combination of those identities. If you take one of them away, I’m no longer the Sparrow you see before you today.

When you look at my privilege this way, you can see that my white privilege is not the whole story. Way out there on the edge where I am nothing but a white person, there is a lot of privilege. The place where the race circle overlaps with the circle indicating that I’m highly educated is a space with a huge amount of privilege.

My education represents multiple layers of privilege, starting with my birth into a middle-class family with two parents who had been to college. I grew up learning things from my parents because they are also highly educated. Growing up in that family also meant I got good nutrition in childhood to help my body grow strong. I got to travel on vacations and have broadening experiences in places other than the neighborhood and community where I grew up. I lived in safe neighborhoods with good schools. I was able to go to university and earn degrees because of many intersecting (there’s that word again) privileges that go all the way back to my childhood. The good nutrition and intellectual stimulation as a child helped my brain to grow in ways that made it easier for me to educate myself. There’s a massive amount of privilege contained in the intersection of those two identities: white and educated.

But what about those other two circles? I am poor and homeless and that often makes me life very difficult. This week I have been going around to places like the Salvation Army, trying to find enough food to keep myself alive until I can either get paid for some of my writing or my next disability check comes in — and I am currently very worried about my disability income because I’m up for re-certification and I filled out the paperwork today and it doesn’t look good. If I lose my SSI disability, I have no idea how I will be able to hold my life together at all. That’s not privilege, right? My homelessness and poverty are the opposite of privilege. A lot of my humanity doesn’t matter to a lot of people in this world if I can’t pay bills or afford the basics of life.

And I am Autistic, as you likely know since this is a blog where I focus on Autistic issues and talk about my lived experience of autism. There is a lot of stigma connected to being known to be Autistic. A lot of people refuse to listen to anything I have to say. A lot of people value what non-autistic people say about autism much more highly than what those of us who live Autistic have to say about it, even when we’re saying the same thing. Most especially when our lived experience is not what the non-autistic experts say it is.

When you look at the space where Autistic and homeless overlap, you realize there is a huge lack of privilege there. Often I need things because I’m homeless that I can’t get because I’m Autistic. Or I need things because I’m Autistic that I can’t get because I’m homeless. My medical care is deeply substandard because of this intersection of lack of privilege. I have a lot of struggles with trying to build a career (ironically, since I chose to become homeless because it was the only way someone at my extremely low income-level could do the work I now do.)

But here’s the thing about intersectionality: that intersection of poverty and homelessness and being Autistic does not erase that intersection of being white and highly educated. I am still privileged at the same time that I am not privileged. I know, right? It can get confusing. But the thing about intersectionality is that I am not just one or two of those intersections of identity but I am all the intersections. When I am struggling to get my healthcare needs met because I am Autistic and homeless, I have an advantage over many other homeless Autistics because I am also white and highly educated. So there are doors that I can open with my privilege even though I am also a marginalized person.

Last summer, I was camping at a free equestrian camp in northern Missouri. There are a ton of those free camps scattered all across the northern part of the state…so many, in fact, that I counted and saw that a person could live for a full year for free, moving from horse camp to horse camp and staying a week at each one, without ever staying at the same camp twice. They are fairly primitive camping spots because they’re mostly there so that people with horses have someplace to go ride them.

My campsite on that particular evening had a fire ring and a picnic table, plus the site had a dumpster and a vault toilet (a big outhouse, basically.) There was no running water, no electricity…and no people. I had a great time there because I was alone for most of that week. Someone parked near me for a few hours to take their horse out of a trailer and ride him around and then left. I really enjoyed the solitude.

One night, a police officer pulled up to my campsite. He asked me if I had heard gunshots. I answered honestly that I had not, and that I had been in my van for the last hour, so I wouldn’t have heard them anyway. I have no idea if there were really gunshots or if that was just his way of opening a conversation with me. He asked me what I was doing and he was pretty friendly about it. I told him the truth: I was on my way to spend the Fourth of July holiday with family but, “you know how it is: I don’t want to show up so early that they’re tired of me before the holiday even starts! So I figured I’d spend a little time camping. Really nice campsite you’ve got here!”

He laughed with me about the idea of imposing one’s self on family too long and agreed that Missouri sure was pretty. Satisfied that I hadn’t decided to permanently move in and that I seemed to be just an innocent traveler, and not up to no good, he wished me a good evening and left.

After the officer left, I wondered how that encounter would have gone if I were Black. Would he have been so quick with the friendly banter? Would he have been so quick to decide it was okay for me to camp there? What if I were not from a highly educated middle-class family? The words that come out of my mouth tell people that I come from a particular background and many people respect me when I am speaking well. What if my stress levels and anxiety had been so high that my Autistic tendency to lose speech in difficult times had kicked in and I wasn’t able to speak smoothly with him? What if I had been in one of my moments where I can’t speak at all and had to type my half of the conversation to him on my AAC device?

This is intersectionality of privilege: the way I was treated by that police officer showed me that he was seeing my privilege and feeling comfortable about me because of it. I could easily have been in a situation where he mainly saw my lack of privilege and felt concerned about my presence at the campsite, wanting to chase me out of his county or put me in his jail or take me to a mental hospital. And if I had been a different person — perhaps one who had a harder time hiding my lack of privilege…say because it was predicated on my dark skin color that I could not hide from him no matter what … it is anyone’s guess how that interaction would have gone.

This is why we talk so much about white privilege when we discuss privilege, even though there are so many different kinds of privilege. Being Black is something a person can’t turn on and off, can’t disguise, can’t just keep their mouth shut about, can’t see a voice coach to learn how to obscure it. Black is Black, no matter what. And that’s a great thing, and something to be pleased and proud of…but it’s also a facet of a person’s identity that means they have to be careful with every single life choice.

Being Black is a facet of a person’s identity that means they live with a target on their back every day, every moment. The wrong word, the wrong movement, going to the wrong place, wearing the wrong clothes, walking home the wrong way on a dark rainy night with your hood up to keep the rain off your head … every single thing that Black people do or say can put them at risk because Blackness is the first thing that people see about them and people make judgments and decisions based on that.

And that is why white privilege is such a huge thing, even for someone like me who is poor, hungry, homeless, multiply disabled, struggling to get by with anxiety and PTSD and a history of abuse and institutionalization. The cards are stacked against me…but my skin is white and my words, when they are working for me, instantly reveal my level of education and privilege and that has kept me alive against the odds for fifty years.

The next time you see someone talking about privilege and you feel angry or ashamed and want to reject the idea that you have privilege? Don’t. Accept that you have privilege. Admit it. Own it. Privilege is not something to be ashamed of. Most of us didn’t even ask for the privileges we have; we were just born that way or born into an environment that was aimed toward shaping us that way. “Check your privilege” doesn’t mean to be ashamed of what you have or of the advantages it gives you.

Being asked to check your privilege just means that you should stop to think about the things that seem easy for you and remember that they are not easy for everyone. You may make phone calls with barely any effort, but it can be hell for me and impossible for someone else. I can drive really well: I’ve driven 31,000 miles in the last 18 months and have only put a few light scuffs on the car in the process (that one-lane tunnel in Indiana was way too narrow, I swear to you!) Not everyone can drive so well or even at all. I’d go so far as to say that at least half of my friends cannot drive at all. Maybe even more than half of them. I am not ashamed that I can drive, but it is important that I check my privilege and remember that it’s not something everyone can do (and there’s no shame in not being able to drive, either!)

If you feel like people want you to feel guilty for being white, stop and ask yourself if you are projecting your own feelings onto them. I have been told to check my white privilege a lot of times and I have never felt like someone wanted me to be ashamed of being white (or of having any sort of privilege). Being ashamed of being white (or privileged in any other way) accomplishes nothing! If you are having a hard time getting past that feeling, though, it can be very therapeutic to use your privilege to help break down the barriers that other people face. Here are some suggestions of ways to use your privilege for the benefit of marginalized people:

Seven ways to use your cisgender privilege (the privilege of being born the sex/gender you identify as being) to help transgender people.

Four ways to “push back” against your privilege (of any type) and help marginalized people.

What to do instead of just feeling guilty about it once you realize you have privilege in some area of your life.

Five ways to use your privilege to fight anti-Black racism.

And, just for good measure, a white cis man explains why wearing a safety pin is not enough.

So don’t resent it when someone lets you know about your privilege. They are helping you to understand yourself better. You are not supposed to feel ashamed. Someone said, “people tell me to check my privilege to get me to shut up” and that’s kind of true. Because as some of those links I just gave you will remind you, when someone reminds you of your privilege that’s the time to stop talking, start listening, and learn about the realities of someone else’s life.

I have learned so much when I have listened to my Black friends, my Latinx friends, friends who are trans women, friends with psychiatric disabilities I don’t have, friends with other disabilities I don’t live with, immigrant friends, friends much older or much younger than me. I have learned so much when I let people tell me about the marginalized aspects of their lives.

When someone helps me check my privilege, they are doing me a favor. It might sting in the short term, but I benefit so much in the long run. We all benefit from understanding the realities of the lives of people who are not the same as us. And we all benefit from increasing access for everyone and working to build a world that is more understanding, more fair, has more opportunities and less stigma and bigotry.

Do you have privilege? Probably, yes. Most people have some amount of privilege and some amount of lack of privilege. It’s not a contest and it’s not a zero sum game. Don’t get caught up in trying to calculate how much privilege you do or don’t have. Accept that you have some privilege and do what you can to help marginalized people (including yourself, if you are marginalized in aspects of your life) get heard and respected.

We are stronger together, all of us. Check your privilege and then use that privilege as a force for good in the world.

Recent Comments